In today’s turbulent economy, one question keeps rising across search trends: Why do the rich keep buying art while millennials can’t afford to participate? The answer lies in how the art market has transformed into a strategic wealth tool for high-net-worth collectors, even as younger generations face rising costs, student debt, and limited investing access. As stocks dipped earlier this year, wealthy buyers flocked to artists like Guy Stanley Philoche—not for décor, but for financial stability. Their purchases moved directly from studio crates to storage, underscoring a reality shaping the global art economy: art is becoming a “safe asset” for already secure investors.

For artists like Philoche, the new demand isn’t surprising. His core buyers—mostly in their 40s and 50s—view art like part of a diversified portfolio, not a luxury. Once a painting consistently sells in the five- and six-figure range, he says, it becomes a commodity. Every sale is followed by deliberate press strategy, controlled scarcity, and strict resale clauses designed to protect long-term value. With each series capped at 60 pieces and unsold works destroyed, the supply remains tight and prices remain stable. It’s a system modeled after corporate economics, not art-school tradition, giving wealthy collectors a predictable asset—and leaving younger buyers unsure how to enter the market at all.

Many millennials and Gen Z professionals express the same frustration: art feels inaccessible, expensive, and culturally distant. The headlines spotlight multimillion-dollar auctions, celebrity collections, and Basel parties, not pieces priced in the hundreds. Philoche argues that opportunities do exist—but timing and knowledge matter. By the time an artist trends online, the price has already skyrocketed. Wealthy families with decades of art-collecting literacy have the advantage, passing down networks, confidence, and early access. Meanwhile, many Black and brown millennials come from households where art collecting was never modeled as a legitimate path to wealth.

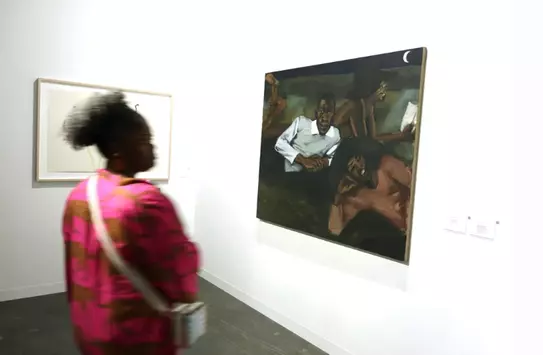

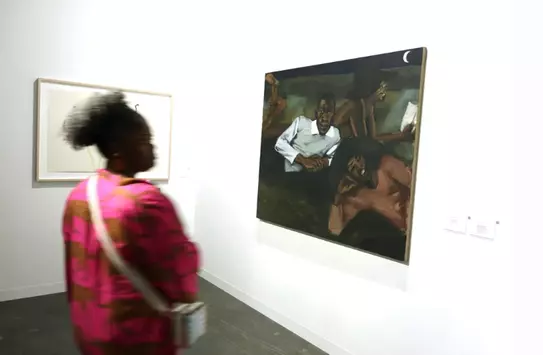

This gap becomes even more striking when the culture represented in the artwork differs from those who ultimately own it. Philoche’s Give Us Our Flowers series celebrates Black aesthetics and identity, yet many buyers remain wealthy and white. Even with buy-back clauses that guarantee investment security, many Black millennials still hesitate to view art as an appreciating asset like real estate or retirement accounts. Without generational exposure to art ownership—and without guidance on insurance, negotiation, and valuation—the community’s wealth potential diminishes while cultural ownership slips away.

Adding complexity is the rise of TikTok creators, influencers, and young entrepreneurs earning five to eight figures annually. They have money and enthusiasm, but not market literacy. Traditional galleries often overlook them, prioritizing legacy collectors and corporate clients. Artists like Philoche and operators like Noir Art House founder Ian Swain see both the potential and the gap. They argue that first-generation collectors need transparency: clear pricing, education, and open conversation. Without this support, millennials with resources still feel like outsiders in a world governed by unspoken rules.

Swain and his co-founder Akilah Ensley see this disconnect daily. Millennials—especially Black millennials—often walk into galleries feeling unwelcome, uninformed, or embarrassed to ask basic questions. The art world has long relied on opacity to maintain prestige, which inadvertently keeps entire communities from participating in wealth-building opportunities. Ensley notes that even with professional success, she initially lacked the knowledge to negotiate, insure, or assess long-term value. The result is a generational freeze-out: appreciation without access, interest without a roadmap.

Philoche’s newest series, Higher Learning, highlights this tension by centering Black students at major universities and HBCUs. At a moment when institutions face political backlash over DEI and history curricula, he frames education as resistance—and visibility as empowerment. The paintings challenge the boundaries of who belongs in elite spaces, including the art market itself. Ownership becomes more than a financial transaction; it becomes a claim to narrative power.

For millennials watching skyrocketing auction prices from afar, the divide may feel permanent—but it doesn’t have to be. The wealthy will continue treating art like a strategic asset, but a new movement is urging the next generation to participate as owners, not spectators. With artists crafting fairer resale practices, galleries embracing transparency, and new collectors seeking guidance, the door may finally be opening. The question now is whether Black and brown millennials—long excluded from these systems—will be supported in stepping through it.

𝗦𝗲𝗺𝗮𝘀𝗼𝗰𝗶𝗮𝗹 𝗶𝘀 𝘄𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗽𝗲𝗼𝗽𝗹𝗲 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝗻𝗲𝗰𝘁, 𝗴𝗿𝗼𝘄, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗳𝗶𝗻𝗱 𝗼𝗽𝗽𝗼𝗿𝘁𝘂𝗻𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗲𝘀.

From jobs and gigs to communities, events, and real conversations — we bring people and ideas together in one simple, meaningful space.

Comments